A portable device used to detect and suppress a carbon monoxide outbreak by filtering contaminated air

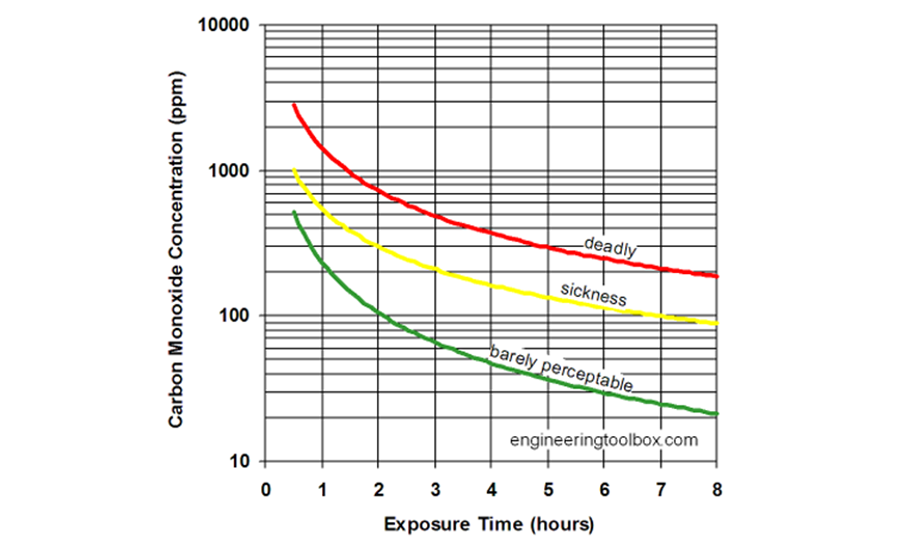

The Carbon Monoxide Suppression Device was developed as part of a 4 person, senior design group at Stony Brook University and had the intention to address the problem of carbon monoxide (CO) exposure in residential environments during a leak. Since CO is an extremely toxic gas that is colorless, odorless and tasteless, emissions of the gas are dangerous to anyone who inhales it. Exposure to CO over a prolonged period of time can be potentially deadly at levels over 100 PPM. Currently, there are only devices available to detect CO in residential dwellings, but nothing that eliminates or suppresses it. This system was aimed to prevent illnesses and/or deaths caused by CO exposure. The design was composed of three major components: an airflow generator, filters containing a gold based oxidation catalyst, and the overall encasement of the system.

Inception

The concept for a Carbon Monoxide Suppression Device was originally inspired by one of the members of the group who was an active volunteer firefighter at the time. Recalling the lengthy and inefficient process of dealing with CO leak calls, he suggested creating a way to improve the system. Over time, as our group conducted more and more research, speaking with specialists and reading scholarly articles in regards to the process of removing CO, we fleshed out an idea. We eventually zeroed in on 2 existing technologies: a catalytic converter (found in almost any gas operated vehicle) and what's called a 'dry scrubber' (commonly used in industrial facilities to filter toxic gas). Both of these devices function by converting 'contaminated' gases into more benign ones through a catalytic reaction with another element.

A design was finally chosen when factoring in the most major parameter of the device: sufficient functioning in an ambient atmosphere (room temperature, regular humidity). A catalytic converter worked, but the materials used to produce a chemical reaction that would eliminate CO would require temperatures well over ambient atmosphere to be effective. A dry scrubber would also work in theory but requires high pressures and large components, making it more practical in commercial settings. Eventually, we landed on a new technology, known as NanAuCat, that utilizes nano gold particles to harness a catalytic reaction that eliminates CO in an ambient atmosphere.

Design

What was important when considering the design of the device was installation, maintanence, and portability. Because the device was to be used in a residence, we wanted to make sure that it did not require a specialist and was functionally understandable by the user.

Functional Specifications

- Develop a prototype that is capable of reducing lethal levels of carbon monoxide in a confined space (i.e. boiler rooms, crawl spaces, basement partitions, etc.) to a non-lethal level of 50 parts per million (PPM) or less

- The device will work in conjunction with a CO sensor and will be a primary suppression device for CO leaks in a residence

- The device is intended to be operable by a homeowner and will not require a technician or specialist to install the device; it will simply be placed, plugged in, and activated.

Physical Specifications

- Size: 30 x 18 x 18 cubin inches

- Weight: <50lbs.

- Flow Rate: 350 – 500 cubic feet per minute (CFM)

- Room Volume: Up to 5000 cubic feet

- Full Room Circulation: <20 minutes

- Minimum CO Level: 50 PPM

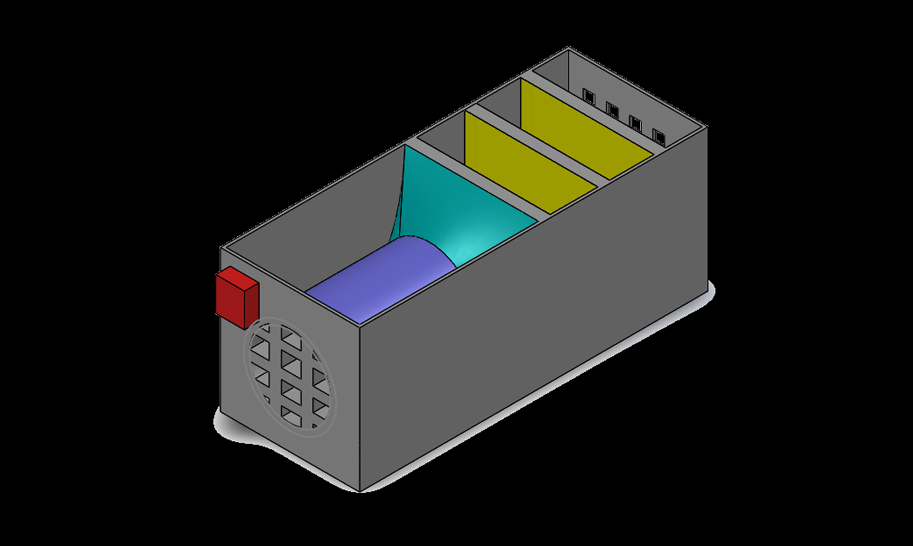

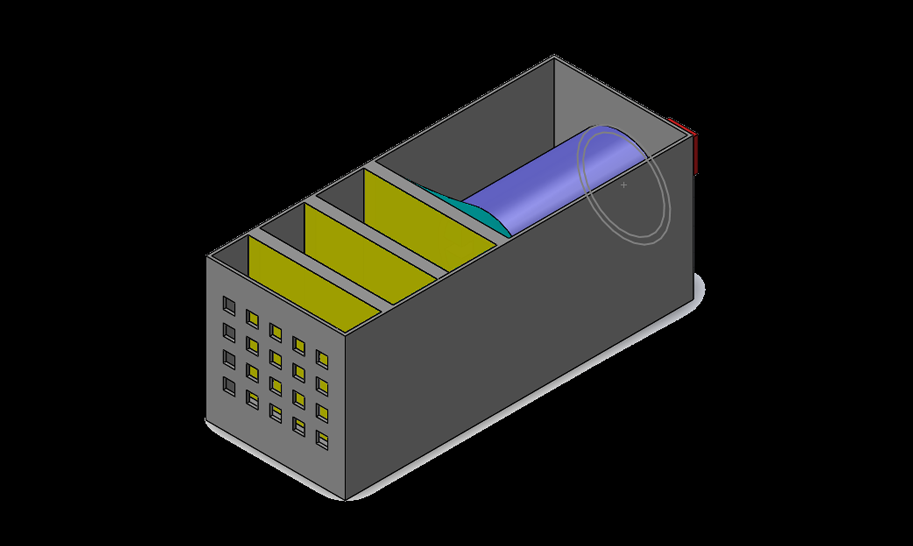

The device consisted of 4 primary components: the CO catalyst, a blower fan, a CO sensor, and the housing. Once the CO sensor is triggered, the blower fan would activate and begin intaking air from the rear, pushing it through 3 layers of our nano-gold-filter, before exiting through a mesh grate at the other end.

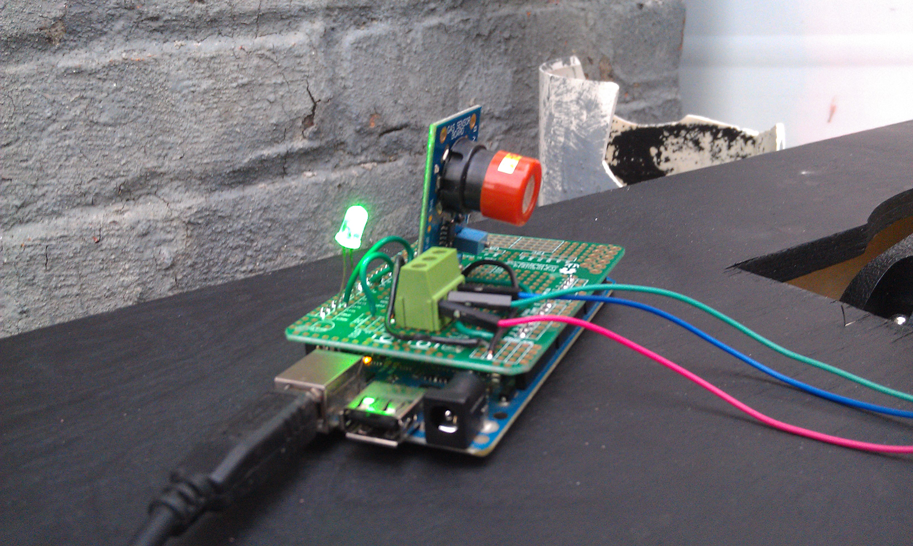

The CO sensor was programmed with an arduino kit and detected levels between 20-2000ppm. The nano-gold-filter comes as a powder in a neutral state, but we were specifically interested in utilizing the AUROlith brick, which very much like a catalytic converter, uses a fine lattice structure to hold the catalyst and maximize the surface area while maintaining airflow; perfect for our application.

Construction

Construction of the device was carried out over the course of a week and consisted of building the housing, manufacturing support slots to hold our nano gold bricks, and assembling all other components.

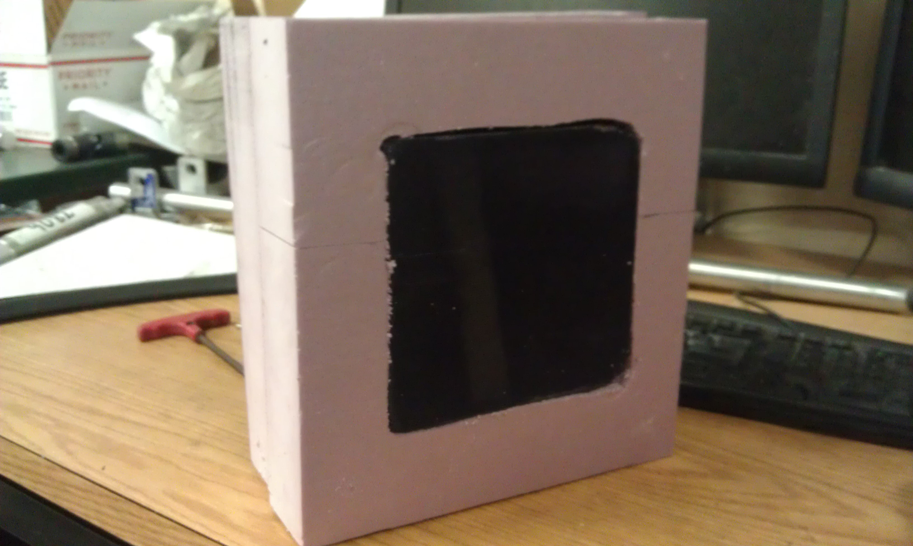

While initially intending to create a prototype out of plexiglass, we ended up compromising with wood due to limited tools and resources. The support structure used for housing the AUROlith brick was foamcore and was cut to precision using a mill.

Once inserted into the supports, the AUROlith brick could simply be inserted into the main housing, creating a nearly airtight seal between each of the components. An air filter was added to the intake of the device to additionally filter large particles that may clog the tiny holes of the catalyst brick. This was later dropped however, due to the significant loss in air pressure.

Testing

The testing of the device was not done outright. It was necessary to first complete all subsystem and component testing before full testing took place. For subsystem testing, the CO sensor, connections between the carbon monoxide sensor and the fan, and the airflow levels of the blower fan all needed to be tested before field testing.

Under ambient conditions, a human can only undergo an exposure of CO at 400-600 PPM (not unusual in a typical household leak) for between 4-6 hours before the risks become fatal. Because CO is odorless, tasteless, and colorless, exposure over that period is not unrealistic either. With our powerful yet, compact blower fan, we are able to produce up to 500-600 CFM of airflow. Using our initial constraints, we would ideally be able to reduce similar CO levels to a safe level in a 5000 cubic foot room in under 20 minutes.

For our test, the CO producer and space used, was a small gas powered generator and 1310 cubic foot metal shed, respectively. 5 trials were conducted for testing: 1 test at levels of approximately 100 PPM to make sure our design works, 1 control test to determine seepage of the room, 2 functionality tests at 200PPM to ensure consistency, and 1 test at 700+ PPM to see how the device operates under extreme conditions. This all took place at a local firehouse which additionally supplied us with a BW Honeywell GasAlert Extreme H2S CO detector to measure the CO levels in the shed.

Results

After testing and reviewing the results, we first had to consider any environmental factors or malfunctions that may have impacted results while testing. Throughout the course of the experiment, we experienced some inconsistency with the supplied CO detector used to measure the levels in the shed. This may have been due to a phenomenon known as sensor saturation, where the sensor retains CO between uses and gives an inflated reading. While this did have an effect on how thorough we wanted our tests to be, we still were able to have a few trials with normal functionality. The other factor that may have impacted our results was the shed having 2 vents. It's unlikely this skewed the results given how small they were, but this wouldn't be known until tested against a sealed space of the same size.

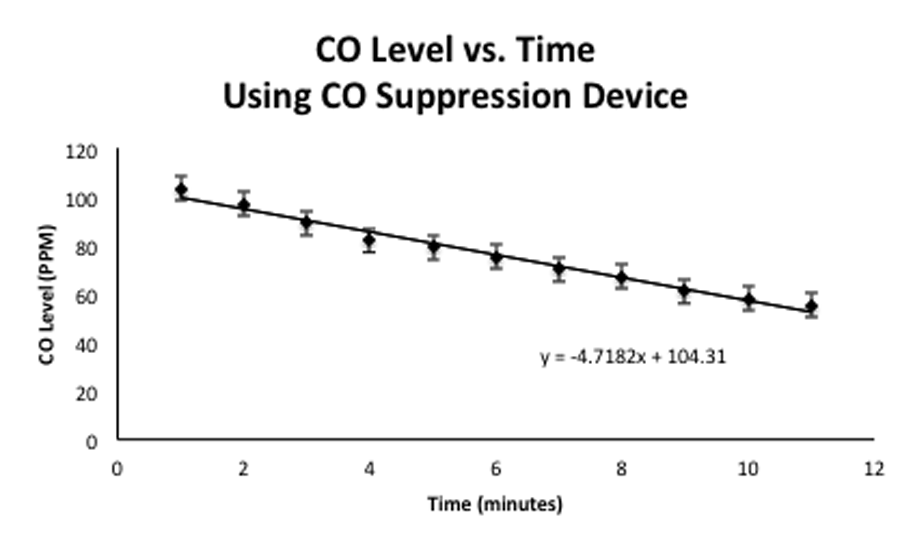

The overall result of our test concluded that our device did work and meet our design goals, but did not do so comfortably due to the issues mentioned previously. It was found that the device oxidized CO at a rate of approximately 4.7PPM per minute, which ultimately met our design goal of reducing CO levels of 100PPM to less than 50PPM within 20 minutes. Based on this successful test, CO levels were reduced from 106PPM to 50PPM in less than 12 minutes.

If future testing were to be conducted, we would want to be more prepared and have a more controlled environment. Having multiple CO detectors and testing in several, sealed spaces of varying sizes would ensure our results would be more consistent. The next step would be field testing the device in real world situations. This testing would occur during a CO call that the fire department would be called to.

This project was another great example of understanding the development process from start to finish. While the lack of specific roles may make some cringe, it helped us maintain the same level of understanding and where one might fit in better than another given their innate skill set. Having a fair amount of freedom with this project also gave us the opportunity to approach the problem the way we desired and coordinate ourselves accordingly.